New guest blogpost about functional hamstring rehabilitation!

I am very excited and honoured that Tom Goom wanted to write a blogpost about hamstring rehabilitation.

Check out his awesome website: running-physio.com.

Great information there!

Tom Goom is a physio, researcher and lead lecturer on the Running Repairs Course. He’s written extensively on running injury management and prevention and recently published a narrative review on Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy. You can follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

Today he talks about functional hamstring rehab! 🙂

A little while ago I posted the video below on the Running Physio Facebook page and a couple of interesting things happened…first of all it went a bit viral with over 60,000 views and secondly it prompted a heated debate on Trust Me, I’m a “Physiotherapist”. You can find the video here.

The major discussion point was are these Nordic type exercises ‘functional’ for the hamstring? This blog aims to answer this question and determine what we mean by ‘functional’ and what functional hamstring rehab might involve…

What does functional mean?

In terms of exercises, functional means to replicate the function itself. Unfortunately people tend to approach this with a fairly narrow view and think that only exercises that replicate the movement pattern are truly functional i.e. It needs to look a but like the function itself in order to be functional. This can lead to a somewhat restrictive approach to exercise selection….

…Working the glutes in side-lying? Nope, not functional!

….Strengthening the hamstrings in kneeling e.g. Nordics? Nope, not functional!

…Building the quads with seated knee extension? Definitely not functional!

Many will point to the principle of Specifity and say an exercise needs to be specific to the function to be effective and this may well be true but there is far more to function than just replicating the movement pattern. Instead we can be specific to function by matching:

- Load magnitude

- Contraction type

- Movement speed, direction and range

- Achieving tissue characteristics needed for function e.g. Stiffness, fascicle length etc

The challenge is identifying which of these is key for each individual and how to target them during rehab. It’s also fair to say few things replicate function like the function itself. Take for example a single leg squat, many might think of it as a ‘functional’ exercise for runners as it replicates some of the movement pattern we might see during impact. This may be true but the entire stance phase of running typically takes less than a third of a second and utilises the stretch-shortening-cyle to achieve propulsion. Are we really replicating this by bending up and down on one knee for a bit!?

While rehab exercise can aim to replicate function, and single leg squat could well be included in these exercises, it’s essential we include a graded return to the function itself alongside our rehab.

What does the hamstring do during function?

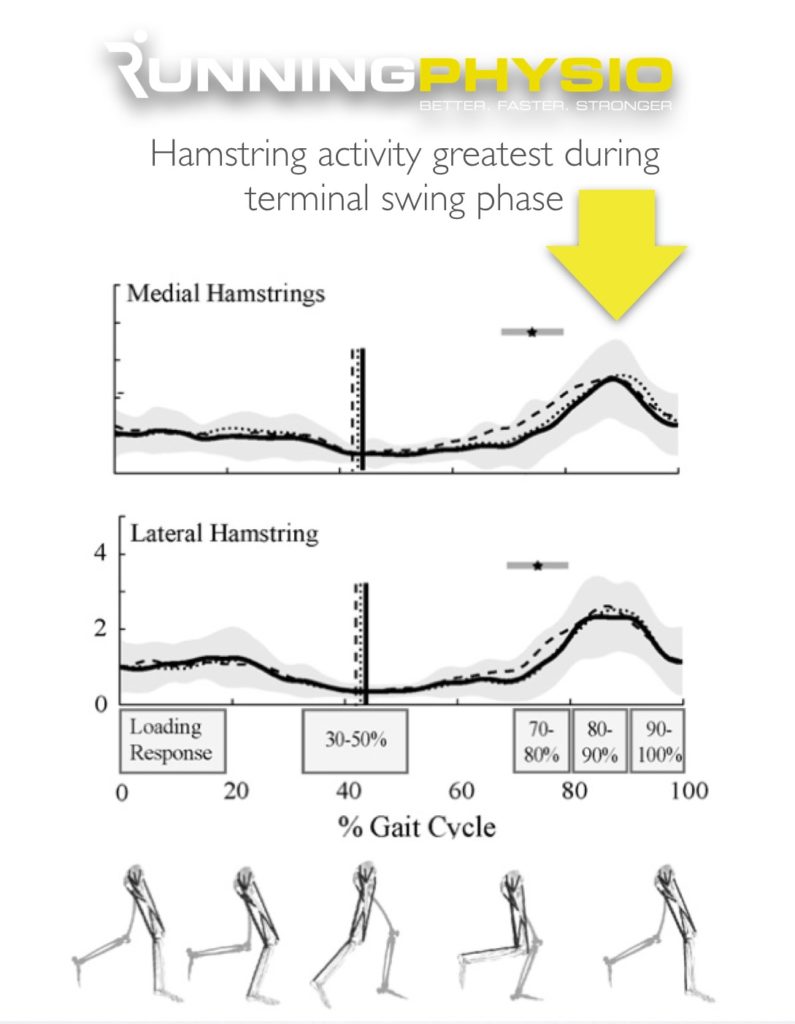

Hamstring function will vary depending on the demands of sport and daily life. We’ll consider running as this is then applicable to many sports. During running the hamstring’s main role is to work eccentrically to decelerate the lower leg at the end of swing phase. EMG studies such as Chumanov et al. (2012) (below) indicate a peak in hamstring activity at terminal swing, prior to foot strike. There’s also a second, smaller peak in activity during the stance phase as the hamstring co-contracts with the quads to support the knee. In sprinting, acceleration, decceleration and uphill running we may see much larger forces on the hamstrings. High-speed running has been linked to hamstring injury and has been found to be the injury mechanism for over 80% of hamstring injury in elite football (Timmins et al. 2015). Large or rapid increases in high-speed running distances has also been found to increase hamstring injury risk (Duhig et al. 2016).

Image adapted from Chumanov et al. (2012)

The hamstrings are frequently exposed to large eccentric loads and need to have the strength, flexibility and tissue characteristics required to manage this load. Functional rehab then will be attempting to achieve this, largely through exercises with a focus on high load eccentric hamstring activity to match the demands of the sport. One exercise that appears to achieve this well is Nordic Curls. While they may not replicate the movement pattern they do expose the hamstring to a large eccentric load which may be why research has found them to be effective in hamstring injury prevention (Malliaropoulos et al. 2012).

Recent research (Timmins et al. 2015) indicates that reduced Biceps Femoris long head (BFlh) fascicle length and reduced eccentric hamstring strength are associated with an increased risk of hamstring injury (HSI). The stats are compelling!…

“For every 0.5cm increase in BFlh fascicle length, the risk of HSI was reduced by 73.9%.”

“For every 10 N increase in eccentric knee flexor strength, the risk of HSI was reduced by 8.9%.”

Fascicle length is measured using ultrasound and not something many of us can do in a clinical setting but it is something our exercise selection can potentially change. Eccentric biased exercises help to increase fascicle length (O’Sullivan et al. 2012) as well as eccentric strength, making them especially useful for preparing for function and reducing injury risk. They are also associated with a more rapid return to sport than traditional concentric based exercises (Askling et al. 2013). Concentric exercise appears to reduce fascicle length so including the concentric component in an exercise may reduce some of the lengthening effects (Timmins et al. 2016). Reducing load during the concentric movement or performing it with two legs, rather than one, may help prevent this.

After hamstring injury isometric strength deficits appear to recover quickly while dynamic strength deficits may exist even after return to play (Maniar et al. 2016). This highlights another key point, a graded return to function may not, on its own, result in a return to pre-injury strength levels.

What exercises might functional hamstring rehab involve?

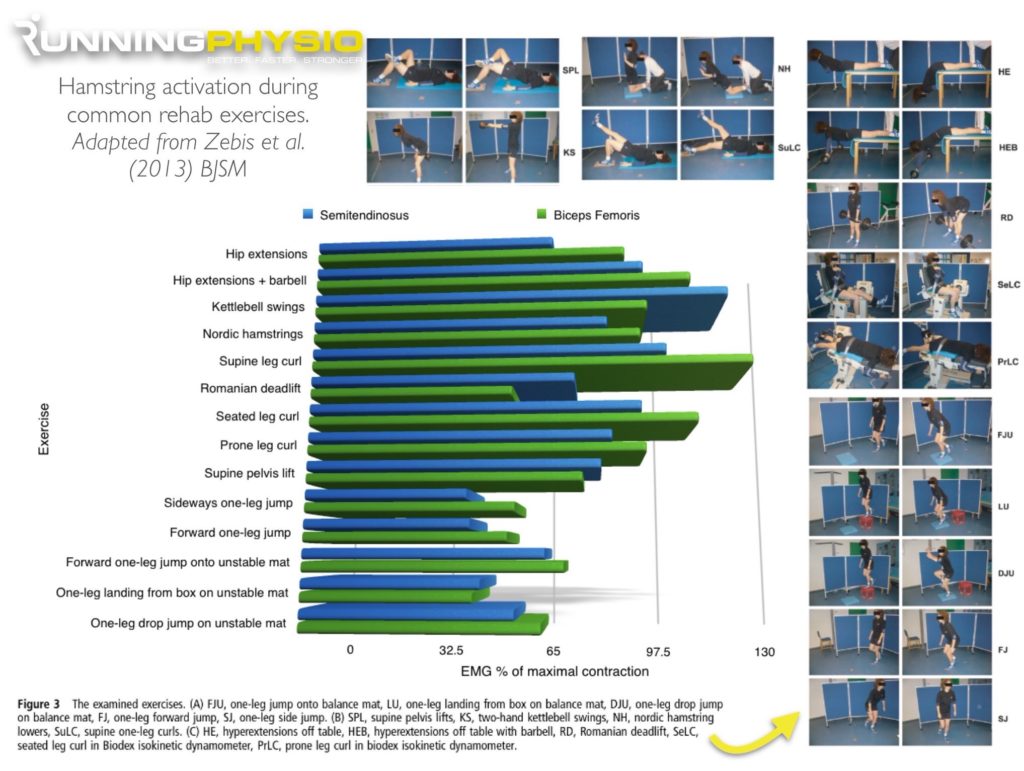

We’ve established that to replicate the demands of function, exercises should ideally involve high load eccentric activity. Over 80% of hamstring tears involve Biceps Femoris (Timmins et al. 2015) so it may be advantagous if our exercises can activate this particular muscle. Recent research (Bourne et al. 2016) suggests hamstring exercises that focus on hip-extension selectively activate Biceps Femoris, while knee flexion based exercises (e.g. Prone hams curl) are more likely to target the medial hamstrings (semimembranosus and semitendinosus). That said, the Nordic Curl, while being an exercise dominated by knee flexion/ extension, is a significant challenge for the entire hamstring complex. EMG studies, such as Zebis et al. (2013) detailed below, give us an indication of which exercises target the hamstring muscles.

Video

The video below shows a selection of functional hamstring exercises;

Here is the video.

More than just the hams!…

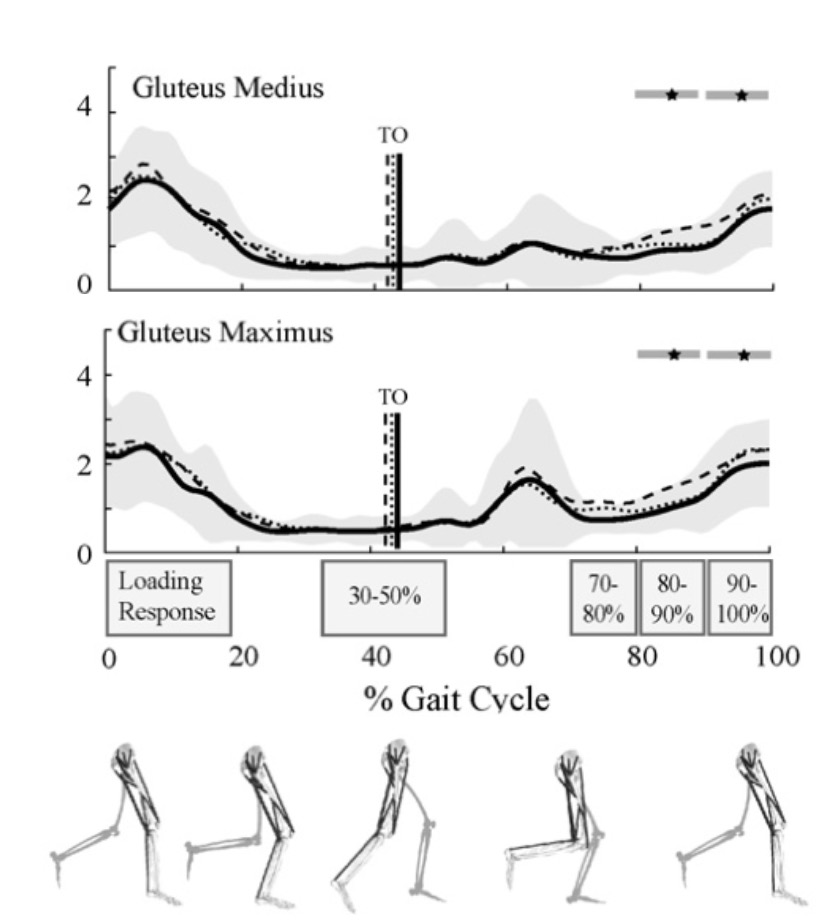

When rehabbing hamstring injury it’s important to think beyond simply strengthening the hamstrings and consider the needs of entire kinetic chain. For example, the adductors are often thought of as the ‘fourth hamstring’ and may assist in hamstring function. The gluteal muscles also show a peak in activity at terminal swing (as shown below) and glute max in particular will assist the hamstrings in deccelerating the limb prior to foot contact. Control of anterior pelvic tilt and hip flexor tightness have also been suggested as further kinetic chain factors that could influence hamstring load and could be a potential target for rehab.

A graded return to sport is important and, in particular, a gradual return to high-speed running. Fatigue may play a part in development of hamstring injury and planning training to allow for a recovery week of reduced high-speed running approximately every fourth week may reduce injury risk (Duhig et al. 2016). Planning the strength training appropriately is important too. Not surprisingly performing Nordics immediately prior to sport has been found to reduce eccentric hamstring strength (during that session) and may increase injury risk (Lovell et al. 2016)! Eccentric exercises are known to create muscle soreness but this tends to improve with time. Where possible periodising training to allow a block of strength training, perhaps in pre-season or when training intensity and volume is lower, may reduce the effects of fatigue on performance.

Closing thoughts: As with most things in health care there are no recipes for hamstring rehab and we must tailor our exercise selection to the needs of the individual. Part of this will be choosing exercises that help prepare that individual for sport and daily functions. Hopefully the evidence above demonstrates we can do this with exercises that don’t replicate the movement pattern itself but may still be functional in terms of contraction type, load magnitude and tissue response.

Much of the recent research in this field comes from QUT-ACU hamstring injury group in Australia, follow them here on Twitter. If you’d like a more in-depth look at hamstring rehab I highly recommend watching this video from Dr Anthony Shield who’s the leader of this group.