Great blogpost by Dale Forsdyke on psychosocial factors in sport! 🙂

Thanks to Tom Goom for letting me share this very interesting post from his website.

Dale is a prominent researcher and practitioner in this field and published an excellent systematic review on the topic (Forsdyke et al. 2016). He’s also Head of Science & Medicine in elite female football and a Senior Lecturer in Sports Injuries. Follow Dale on Twitter via @Forsdyke_Dale.

Psychosocial factors and training error

One area where we’ve seen a great deal of progress in recent years has been an understanding of how important training load management is in injury prevention (see Windt & Gabbett, 2016). Modifying and monitoring training load can have an impact on injury occurrence and reoccurrence but there’s one understated significant barrier…advising an athlete to change their training doesn’t guarantee they actually will! This has led us to wonder, are psychosocial factors a key issue in training load error that we might be overlooking?…

When we look at an injured runner’s training schedule in clinic we usually have 2 broad aims;

- Identify if ‘training error’ has led to the injury e.g. recent training spikes

- Find the right level of training load (the sweet-spot) to suite the runner and their symptoms as a starting point to build from

There’s an issue with this approach though…sometimes the runner ignores your advice and keeps training despite this causing pain. A conversation like this isn’t unusual,

Physio: “How are your symptoms at present?”

Athlete: “No better”

Physio: “Have you modified your training as we discussed?”

Athlete: “Umm, no”

Physio: *dies a little inside*

This highlights an issue we face with education; knowing what to do doesn’t mean you’ll actually do it. Increasing knowledge doesn’t necessarily guarantee behavioural change. Therefore, readiness to change training behaviour might be associated with other psychosocial factors beyond just miseducation. Athletes need to see that the pro’s of modifying their training load outweigh the con’s, with a range of psychosocial factors contributing to the balance between the two.

The problem is though if this runner doesn’t feel able to change their training behaviour and continues to aggravate their symptoms it can be very difficult (if not impossible) to help manage their injury. We need to be prepared to explore the reasons behind their ongoing training behaviour.

Maladaptive beliefs about training

Some athletes overvalue high intensity work and undervalue low intensity exercise, recovery and rest. This means that they participate in high intensity repetitive running leaving them with little or no time to recover or adapt to loading. A study by Madigan et al. (2017) found certain personality characteristics that innately give runners maladaptive beliefs over training (e.g. perfectionism) predicted changes in training distress (a marker of overtraining) over time.

Perhaps the best way to illustrate these beliefs is with a few quotes from runners,

“Unless I’m working hard, 10 out of 10 for every session, I don’t feel it’s worth it.”

“I don’t see the point of rest.” Or the more extreme, “rest is rust!”

“If I train slowly I’ll race slowly.”

Research in optimising performance for endurance athletes questions this need for high volumes of high intensity work. Seiler (2010) suggests approximately 80% of training volume should be low intensity and only 20% high intensity (e.g. Tempo runs and interval sessions). Doing more high intensity exercise may not actually improve performance and may elevate injury risk. Changes in training intensity have been associated with achilles tendinopathy, plantar fasciitis and calf injuries in runners (Nielsen et al. 2013).

Social support and comparison to others

Recent research has highlighted the importance of good social support after injury (Forsdyke et al. 2016). The running culture within your peer group (e.g. running friends, running coaches, on-line running communities) help foster decisions regarding training structure and progression. However, there can be a down side; some runners compare themselves to others and expect to train the same way. I often hear an athlete say, “but Tom, Dick and Harry can run 100 miles a week with no problems”. Of course they’re unaware that Tom, Dick and Harry have all seen me for various injuries! There is significant individual variability in response to loading that runners should be aware of.

Anxiety, stress and negative life events

Sometimes running can be a coping strategy for stress, anxiety and negative events in life. Some runners in clinic have said they’re ‘in crisis’ because their mental health has deteriorated when they’ve stopped running due to injury. Whilst we want to help an athlete maintain physical and psychological wellbeing, we also may need to explore other options for managing their mental health that may allow them to adjust their training without negative consequences. We often are too eager to purely look at the training load of runners without recognising the significance of accumulated load (e.g. the combined loading from training and everything else).

Impact of negative thoughts and feelings

How we think influences how we feel and behave (or in other terms cognitive appraisal). Some runners admit to thinking they are lazy if they aren’t working at 100% all the time. This can lead to them feeling guilty and even ashamed. These runners can feel obligated to continue loading to avoid negative emotions if they cease or modify their loading pattern. In order to avoid these strong, negative feelings they might push themselves to constantly train at a high intensity. This then can lead to high chronic loading or training spikes, with limited recovery, and be a signficant factor in injury development.

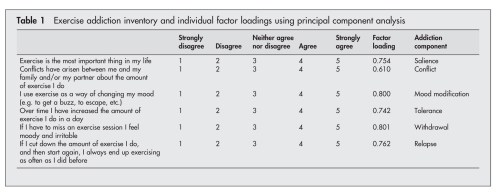

For some such thoughts and feelings may result in ‘exercise addiction’ or a compulsion to exercise (even if they take no pleasure from it). Griffiths et al. (2005) found the Exercise Addiction Inventory to be a quick and easy tool to screen for exercise addiction;

Further research is needed on the clinical use of inventories of this type. If you’re concerned about an athlete’s mental health you may need to arrange a referral to an appropriate mental health professional and liase with their GP. Wherever possible work together in an integrated multi-disciplinary team to provide optimal care.

Runners with a compulsion to exercise or evidence of exericse addiction may find adpating their training following injury especially difficult. They need understanding of the challenge they face and the right support to make these changes.

Miseducation and external pressures

The modern world is awash with information but sadly, much of it is inaccurate and unhelpful. In some environments macho, unhelpful mantras can put pressure on people to push themselves beyond their limits. “Go hard or go home!” is an example of this. Try as I might I can’t seem to get people to change this to, “Go hard during specific training sessions as part of a periodised training programme with appropriate volume, and then go home and optimise recovery!” …Just not as catchy!

In many sports external pressures can come from team mates, coaches and managers. It’s a delicate balance between managing injury risk and achieving optimal performance.

Not all training beliefs will lead to excessive training some might do the opposite…

Fear of discomfort or damage

Some athletes may not want to push themselves to the point of discomfort or may fear causing lasting damage. These beliefs may limit training or prevent return to sport. It’s important to note that undertraining may potentially elevate injury risk. The ‘sweet spot’ described by Gabbett et al. 2016 illustrates this;

Source Gabbett et al. (2016) Open Access.

Fear of high training load

This might be something us clinicians have!! We’ve become wary of high training loads due to perceived high injury risk but it’s important to remember such training has potential benefits too. It can help build fitness, the skills and characteristics needed to perform and both physical and mental resilience. Tim Gabbett, who has done a lot of work in training load management, suggests it’s a balance between fitness and fatigue.

Key, positive messages about loading are the Goldilocks Principle (not too much, not too little, just right) and it’s not necessarily high training loads that are the problem, it’s how you get there.

What’s the answer?

The first challenge is to identify training beliefs that might be unhelpful in runners. This takes honest and open discussion. It might mean asking some tough questions and there may not be easy answers! Such discussions can really help you get to know your athletes which is an important part of working together and building psychological readiness for return to sport alongside physical readiness (Forsdyke, Gledhill and Ardern 2016).

For some athletes spending the whole session discussion training structure and progression may be more beneficial than adding another rehab exercise or massaging the bit that’s sore! This may centre around delivering key, simple messages;

- Change gradually (e.g.10% progression each week)

- Your body will adapt but it needs appropriate recovery time

- Recovery (physical and mental) is important and beneficial for performance

- Plan your training to match your goals and your abilities

- Easy training can be good training!

- Look after yourself – embrace an attitude of self-care

- Your overall loading is more than just the miles you cover and minutes per mile. It is the combination of training and lifestyle (physical and mental) loading

- After periods of detraining e.g. injury, holiday etc. don’t go straight back into high training schedules. This will create a training load spike and may increase risk of injury.

It’s important too to see if these messages are recieved and understood. Once you’ve discussed the key training principles, it can help to put the onus back on the athlete. They should be autonomous human beings after all! Ask, “how might you adapt your weekly training schedule to get the most out of it?”

Perhaps the answer lies not in telling the athlete to adapt training but in giving them the information to make an informed choice. We may be more successful in creating changes in training behaviour if we express empathy and understanding while indentifying the discrepancy between the athlete’s training goals and their current approach to training. This may mean adjusting to resistance from the athlete, rather than opposing it directly and supporting self-efficacy and positive choices.

Such an approach may help us apply the principles of training load management by helping runners successfully adapt their training and optimise it both for performance and injury risk.